Compiling Ruby. Part 0: Motivation

Published on

This article is part of the series "Compiling Ruby," in which I'm documenting my journey of building an ahead-of-time (AOT) compiler for DragonRuby, which is based on mruby and heavily utilizes MLIR and LLVM infrastructure.

This series is mostly a brain dump, though sometimes I'm trying to make things easy to understand. Please, let me know if some specific part is unclear and you'd want me to elaborate on it.

Here is what you can expect from the series:

- Motivation: some background reading on what and why

- Compilers vs Interpreters: a high level overview of the chosen approach

- RiteVM: a high-level overview of the mruby Virtual Machine

- MLIR and compilation: covers what is MLIR and how it fits into the whole picture

- Progress update: short progress update with what's done and what's next

- Exceptions: an overview of how exceptions work in Ruby

- Garbage Collection (TBD): an overview of how mruby manages memory

- Fibers (TBD): what are fibers in Ruby, and how mruby makes them work

For the last couple of years, I’ve been working on a fun side project called DragonRuby Game Toolkit, or GTK for short.

GTK is a professional-grade 2D game engine. Among the many incredible features:

- you can build games in Ruby

- it targets many (like, many!) platforms (Windows, Linux, macOS, iOS, Android, WASM, Nintendo Switch, Xbox, PlayStation, Oculus VR, Steam Deck)

- super lightweight (~3.5 megabytes)

- and many more really

GTK is built on top of a slightly customized mruby runtime and allows you to write games purely in Ruby. It comes with all the batteries included, but if you need more in a specific case, you can always fall back to C via the C extensions mechanism.

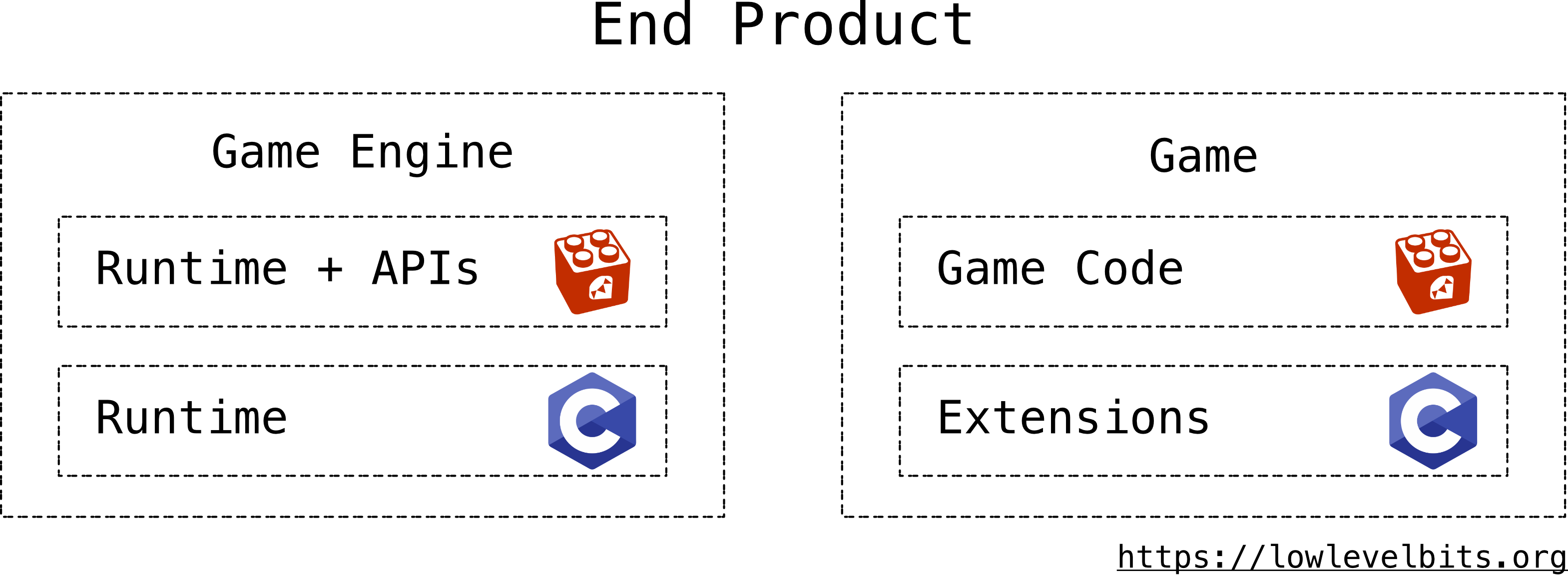

From a user perspective, the end product (the game) looks like this:

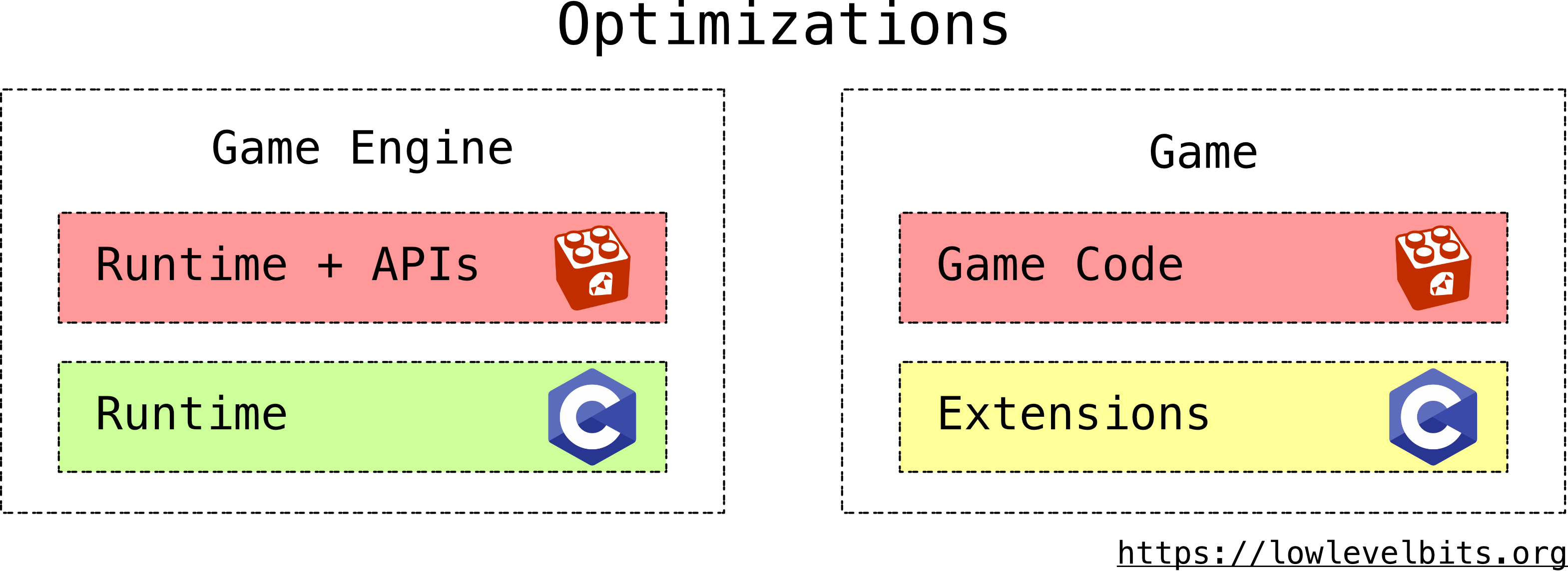

While the engine itself is pretty fast, what annoys me personally (from the aesthetic point of view) is that we cannot fully optimize the C extensions as they are compiled separately from the rest of the engine.

Looking at the picture, we have four components of the game:

- the engine’s runtime (Ruby)

- the engine’s runtime (C)

- the game code (Ruby)

- the game code (C)

Suppose we want to optimize all the C code together. In that case, we’d have to ship the runtime in some ‘common’ denominator form (e.g., LLVM Bitcode), then compile the C extension into the same form, optimize it all together and then link into an executable.

This is doable, but while I was thinking about this problem I’ve found even bigger (and much more interesting) ‘problem’ - what about all that Ruby code? Can we also compile it to some common form and then optimize it with the rest of the C code out there?

The answer is - definitely yes! We just need to build a compiler that would do that job.

At the time of writing, the compiler is far from being done, but it works reasonably well, and I can successfully compile and run more than half of the mruby test suite.

As a sneak peek, here is an output from the test suite:

/opt/DragonRuby/FireStorm/cmake-build-llvm-14-asan/tests/MrbTests/firestorm_mrbtest

mrbtest - Embeddable Ruby Test

............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................?.........................................................................................................................

Skip: File.expand_path (with ENV)

Total: 934

OK: 933

KO: 0

Crash: 0

Warning: 0

Skip: 1

Time: 0.45 seconds

Process finished with exit code 0

I hope this motivation gives you enough information on why someone would do what I am doing!

Let’s take a look at the approach I am taking to solve this problem - Compilers vs. Interpreters