LLVM meets Code Property Graphs

Published on

This is a cross-post from LLVM’s blog post LLVM meets Code Property Graphs

The code property graph (CPG) is a data structure designed to mine large codebases for instances of programming patterns via a domain-specific query language. It was first introduced in the proceedings of the IEEE Security and Privacy conference in 2014 (publication, PDF) in the context of vulnerability discovery in C system code and the Linux kernel in particular. The core ideas of the approach are the following:

- the CPG combines several program representations into one

- the CPG is stored in a graph database

- the graph database comes with a DSL allowing to traverse and query the CPG

Currently, the CPG infrastructure is supported by several tools:

- Ocular - a proprietary code analysis tool supporting Java, Scala, C#, Go, Python, and JavaScript languages

- Joern - an open-source counterpart of Ocular supporting C and C++

- Plume - an open-source tool supporting Java Bytecode

This article presents ShiftLeft’s open-source implementation of llvm2cpg - a standalone tool that brings LLVM Bitcode support to Joern. But before we dive into details, let us say few more words about CPG and Joern.

Code Property Graph

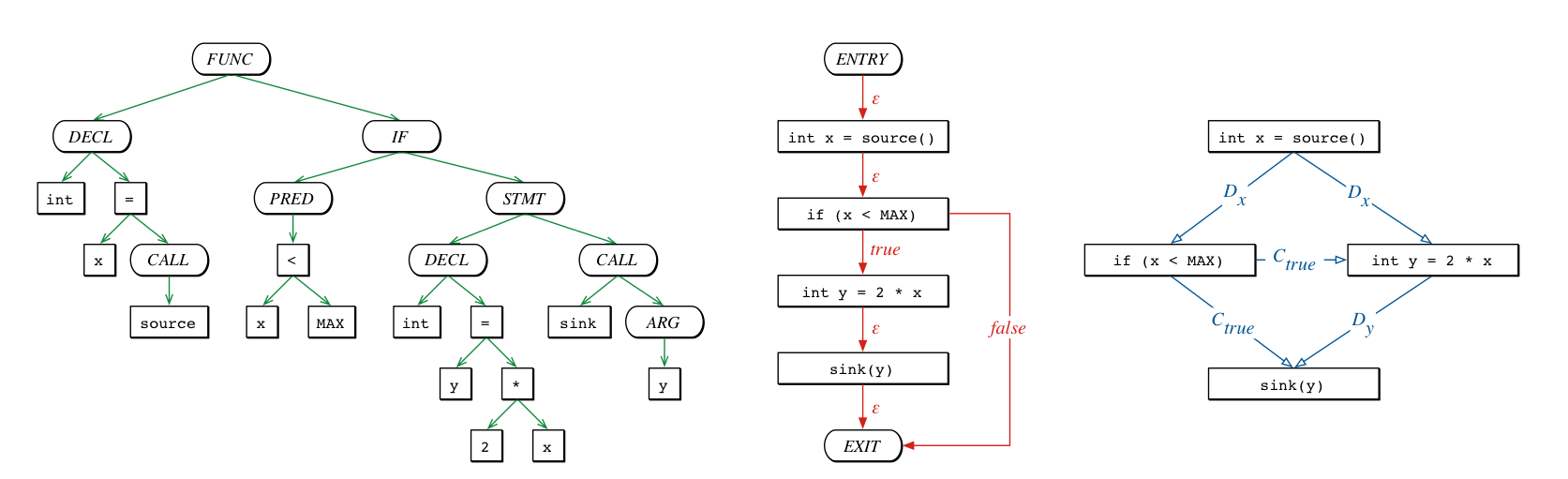

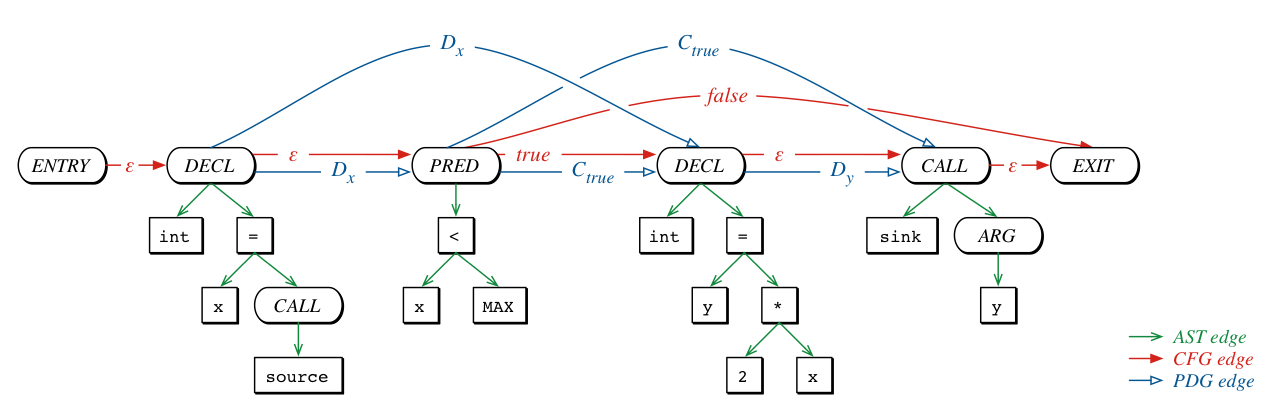

The core idea of the CPG is that different classic program representations are merged into a property graph, a single data structure that holds information about the program’s syntax, control- and intra-procedural data-flow.

Graphically speaking, the following piece of code:

void foo() {

int x = source();

if (x < MAX) {

int y = 2 * x;

sink(y);

}

}

combines these three different representations:

into a single representation - Code Property Graph:

Joern

The property graph is stored in a graph database and made accessible via a domain-specific language (DSL) to identify programming patterns based on a DSL for graph traversals. The query language allows a seamless transition between the original code representations, making it possible to combine aspects of the code from different views these representations offer.

One of the primary interfaces to the code property graphs is a tool called Joern. It provides the mentioned DSL and allows to query the CPG to discover specific properties of a program. Here are some examples of the Joern’s DSL:

joern> cpg.typeDecl.name.p

List[String] = List("ANY", "int", "void")

joern> cpg.method.name.p

List[String] = List(

"foo",

"<operator>.multiplication",

"source",

"<operator>.lessThan",

"<operator>.assignment",

"sink"

)

joern> cpg.method("foo").ast.isControlStructure.code.p

List[String] = List("if (x < MAX)")

joern> cpg.method("foo").ast.isCall.map(c => c.file.name.head + ":" + c.lineNumber.get + " " + c.name + ": " + c.code).p

List[String] = List(

"main.c:2 <operator>.assignment: x = source()",

"main.c:2 source: source()",

"main.c:3 <operator>.lessThan: x < MAX",

"main.c:4 <operator>.assignment: y = 2 * x",

"main.c:4 <operator>.multiplication: 2 * x",

"main.c:5 sink: sink(y)"

)

Besides the DSL, Joern comes with a data-flow tracker enabling more sophisticated queries, such as “is there a user controlled malloc in the program?”

The DSL is much more powerful than in the example, but that is out of scope of this article. Please, refer to the documentation to learn more.

LLVM and CPG

This part is split into two smaller parts: the first one covers a few implementation details, the second one shows an example of how to use llvm2cpg.

If you are not interested in the implementation - scroll down :)

Implementation Details

When we decided to add LLVM support for CPG, one of the first questions was: how do we map bitcode representation onto CPG?

We took a simple approach - let’s pretend the SSA representation is just a flat source program. In other words, the following bitcode

define i32 @sum(i32 %a, i32 %a) {

%r = add nsw i32 %a, %b

ret i32 %r

}

can be seen as a C program:

i32 sum(i32 a, i32 b) {

i32 r = add(a, b);

return r;

}

From the high-level perspective, the approach is simple, but there are some tiny details we had to overcome.

Instruction semantics

We can map some of the LLVM instructions back onto the internal CPG operations. Here are some examples:

add,fadd-><operator>.additionbitcast-><operator>.castfcmp eq,icmp eq-><operator>.equalsurem,srem,frem-><operator>.modulogetelementptr-> a combination of<operator>.pointerShift,<operator>.indexAccess, and<operator>.memberAccessdepending on the underlying types of the GEP operand

Most of these <operator>.*s have special semantics, which plays a crucial role in the Joern and Ocular built-in data-flow trackers.

Unfortunately, not every LLVM instruction has a corresponding operator in the CPG. In those cases, we had to fall back to function calls. For example:

select i1 %cond, i32 %v1, i32 %v3turns intoselect(cond, v1, v2)atomicrmw add i32* %ptr, i32 1turns intoatomicrmwAdd(ptr, 1)(same for any otheratomicrmwoperator)fneg float %valturns intofneg(val)

The only instruction we could not map to the CPG is the phi: CPG doesn’t have a Phi node concept.

We had to eliminate phi instructions using reg2mem machinery.

Redundancy

For a small C program

int sum(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

Clang emits a lot of redundant instructions by default

define i32 @sum(i32 %0, i32 %1) {

%3 = alloca i32, align 4

%4 = alloca i32, align 4

store i32 %0, i32* %3, align 4

store i32 %1, i32* %4, align 4

%5 = load i32, i32* %3, align 4

%6 = load i32, i32* %4, align 4

%7 = add nsw i32 %5, %6

ret i32 %7

}

instead of a more concise version

define i32 @sum(i32 %0, i32 %1) {

%3 = add nsw i32 %1, %0

ret i32 %3

}

In general, this is not a problem, but it adds more complexity for the data-flow tracker and needlessly increases the graph’s size. One of the considerations was to run optimizations before emitting CPG for the bitcode. Still, in the end, we decided to offload this work to an end-user: if you want fewer instructions, then apply the optimizations manually before emitting the CPG.

Type Equality

The other issue is related to the way LLVM handles types. If two modules in the same context use the same struct with the same name, LLVM renames the other struct to prevent name collisions. For example

; Module1

%struct.Point = type { i32, i32 }

and

; Module 2

%struct.Point = type { i32, i32 }

when loaded into the same context yield two types

%struct.Point = type { i32, i32 }

%struct.Point.1 = type { i32, i32 }

We wanted to deduplicate these types for a better user experience and only emit Point in the final graph.

The obvious solution was to consider two structs with “similar” names and the same layout to be the same.

However, we could not rely on the llvm::StructType::isLayoutIdentical because, despite the name, it produces misleading results.

According to llvm::StructType::isLayoutIdentical the structs Point and Pair have identical layout, but PointWrap and PairWrap are not.

; these two have identical layout

%Point = type { i32, i32 }

%Pair = type { i32, i32 }

; these two DO NOT have identical layout

%PointWrap = type { %Point }

%PairWrap = type { %Pair }

This happens because llvm::StructType::isLayoutIdentical determines equality based on the pointers. That is, if all the struct elements are identical, then the layout identical.

It also meant we could not use this approach to compare types from different LLVM contexts.

We had to roll out our custom solution based on the Tree Automata to solve this issue.

There are few more details, but the article is getting longer than it needs to be.

So let’s look at how to use llvm2cpg with Joern.

Example

Once you have Joern and llvm2cpg installed the usage is straightforward:

- Convert a program into LLVM Bitcode

- Emit CPG

- Load the CPG into Joern and start the analysis

Here are the steps codified:

$ cat main.c

extern int MAX;

extern int source();

extern void sink(int);

void foo() {

int x = source();

if (x < MAX) {

int y = 2 * x;

sink(y);

}

}

$ clang -S -emit-llvm -g -O1 main.c -o main.ll

$ llvm2cpg -output=/tmp/cpg.bin.zip main.ll

Now you get the CPG saved at /tmp/cpg.bin.zip which you can load into Joern and find if there is a flow from the source function to the sink:

$ joern

joern> importCpg("/tmp/cpg.bin.zip")

joern> run.ossdataflow

joern> def source = cpg.call("source")

joern> def sink = cpg.call("sink").argument

joern> sink.reachableByFlows(source).p

List[String] = List(

"""_____________________________________________________

| tracked | lineNumber| method| file |

|====================================================|

| source | 5 | foo | main.c |

| <operator>.assignment | 5 | foo | main.c |

| <operator>.lessThan | 6 | foo | main.c |

| <operator>.shiftLeft | 7 | foo | main.c |

| <operator>.shiftLeft | 7 | foo | main.c |

| <operator>.assignment | 7 | foo | main.c |

| sink | 8 | foo | main.c |

"""

)

Which indeed exists!

Conclusion

To conclude, let us outline some of the advantages and constraints implied by LLVM Bitcode:

- the “surface” of the LLVM language is smaller than that of C and C++

- many high-level details do not exist at the IR level

- the program must be compiled, thus limiting the range of programs that one can analyze with Joern

Here you can find more tutorials and information.

If you get any questions, feel free to ping Fabs or Alex on Twitter, or better come over to the Joern chat.